The Lister seemed very theory -driven to me, so I will try to sum up some points first, then connect these to the machine in my chosen chapter of Gitelman: the physiognotrace.

‘interactive’ signifies the ability of the user to directly intervene and change the images or text that they access 1. extractive-online shopping: text-base, linear/practical 2.immersive-gaming: visually pleasing, includes screen space~Both are essentially states of mind

Text always brings the problem of interpretation-for example

‘Simulation’-false and illusory, ‘hollow representations of things’ or something in itself

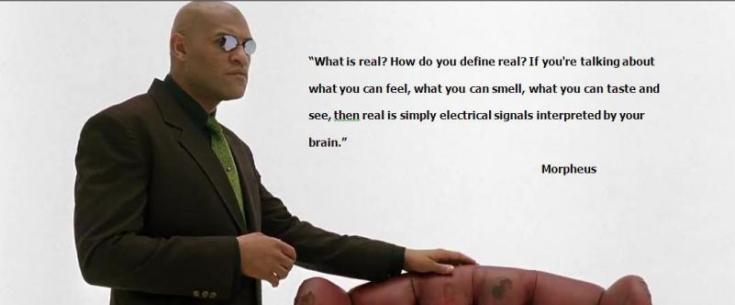

–> gap in perception +reality -always there anyway: Think about Morpheous’ speech in ‘The Matrix’; ‘real’ is electrical signals interpreted by the brain “…a hyperreality where the artificial is experienced as real, Representation, the relationship (however mediated) between the real world and its referents in the images and narratives of popular media and art, withers away, The simulations that take its place also replace reality with spectacular fictions whose lures we must resist. In broad outlines, this remains the standard view of Baudrillard’s theses.” Lister 44 (I think that fear of the loss of ‘the real’ happened to the physiognotrace)

The fact that new=better in most people’s minds, to me, forgets to take into account that gap in perception +reality.–>–v

I think this best sums up the intro to Gitelman and what comes after, and then we can see that communication systems all try to bridge that gap by creating lexemes in a given semiotic economy-“There is a moment, before the material means and the conceptual modes of new media have become fixed, when such media are not yet accepted as natural, when their own meanings are in flux. At such a moment, we might say that new media briefly acknowledge and question the mythic character and the ritualized conventions of existing media, while they are themselves defined within a perceptual and semiotic economy that they then help to transform.”

Gitelman, Lisa; Pingree, Geoffrey B. New Media, 1740–1915 (Media in Transition) (Page xii). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

physiognotrace -19th century Americans questioned how close to reality the pictures were, which is, of course, to bring up the same modern concerns parents have about their kids spending all day on the computer and not having face-to-face encounters with real people. But the real ‘burden of proof’ for the physiognotrace was to harmonize “visual and political representations” by itself: to my mind, it’ not so far-fetched, because we know about the relationship between beauty/attractiveness and expectations from the study of psychology. Indeed, simulation comes up again, defined as a special or temporal representation (I would say both, inseparably, space/time, though, and I think that’s what they ultimately mean anyway) and contrasted with imitation as another method of representation. We learned from Lister that a simulation can be a real thing too, and in fact occupies a space apart, which is no less real. By extension, to imitation we can also give status of referent. I predicted that the gap between what a person looks like and what they actually know/do will be too big to sit comfortably with many people in the case of the physiognotrace (however more attractive people still tend to succeed more).

It becomes complex when applied to a human being who represents another human being, or a group of them. The representation can’t be a simulation because of the referent being multiple and plural, according to the British model. But the American “ideal” of representation was multiple and plural, and the physiognotrace became an artistic representation of this, but the “pseudoscience of physiognomy” was not, it was found, the way to the source of ‘Truth.’ The physiognotrace brought people closer to the two types of interactivity defined above, but it ultimately became part of a failed symbolic economy.

September 8, 2016 at 10:36 pm

What do you mean when you say that the physiognotrace became part of a “failed symbolic economy”?

LikeLike

September 9, 2016 at 10:13 pm

It was eventually revealed to be ineffectual for communication, especially the type of communication that representative politics was the ideal of.

LikeLike